Today, after this week of rapid political and societal change, I want to share two poems from two different poets, who wrote in two different times.

From Kahlil Gibran, in The Garden of the Prophet:

Pity the nation that is full of beliefs and empty of religion.

Pity the nation that wears a cloth it does not weave

and eats a bread it does not harvest.Pity the nation that acclaims the bully as hero,

and that deems the glittering conqueror bountiful.Pity a nation that despises a passion in its dream,

yet submits in its awakening.Pity the nation that raises not its voice

save when it walks in a funeral,

boasts not except among its ruins,

and will rebel not save when its neck is laid

between the sword and the block.Pity the nation whose statesman is a fox,

whose philosopher is a juggler,

and whose art is the art of patching and mimickingPity the nation that welcomes its new ruler with trumpeting,

and farewells him with hooting,

only to welcome another with trumpeting again.Pity the nation whose sages are dumb with years

and whose strongmen are yet in the cradle.Pity the nation divided into fragments,

each fragment deeming itself a nation.

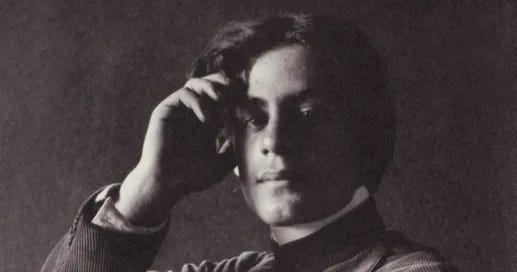

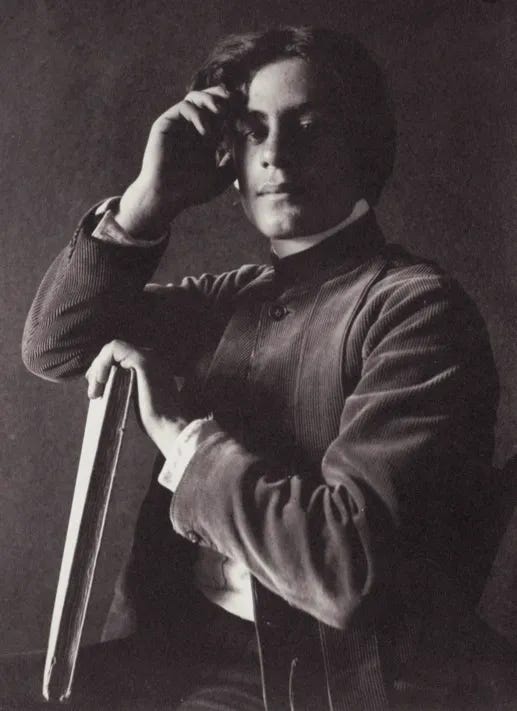

Kahlil Gibran, a Lebanese poet, wrote Pity the Nation, which was posthumously published in his book The Garden of the Prophet in 1933, two years after his death in 1931. The poem reflects Gibran’s deep concerns about his homeland’s societal and political corruption, the loss of freedoms, and the erosion of values. It is both a lament and a critique.

And although it was published nearly 100 years ago, in a different time and place, under a different political regime, it rings eerily true today.

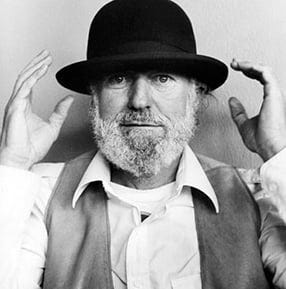

Pity the Nation inspired another poet, Lawrence Ferlinghetti, to write a poem of the same name, which he published in 2007, in his book Poetry as Insurgent Art. Ferlinghetti wrote his version in the post 9/11 era, in response to the political, cultural, and social climate of the United States and the early years of the Iraq War. Here’s his version:

Pity the nation whose people are sheep

And whose shepherds mislead them

Pity the nation whose leaders are liars

Whose sages are silenced

And whose bigots haunt the airwaves

Pity the nation that raises not its voice

Except to praise conquerors

And acclaim the bully as hero

And aims to rule the world

By force and torture

Pity the nation that knows

No other language but its own

And no other culture but its own

Pity the nation whose breath is money

And sleeps the sleep of the too well fed

Pity the nation oh pity the people

who allow their rights to erode

and their freedoms to be washed away

My country, tears of thee

Sweet land of liberty!

While Gibran's poem was more universal in its critique of nations and humanity, Ferlinghetti's version was intended as a pointed critique of America. The two versions are connected by their shared prophetic tone and, hauntingly, their ability to transcend their respective eras.

These poems show courage in the heart of the poet. But they also show an enduring theme that we’ve been dealing with for millennia.

Where in human history have we not endured cycles of struggle against oppression and corruption? Where in history have we escaped the bully as hero, the statesman as a fox, the bigots who haunt the airwaves, and the sages who are silenced?

What brings peace to my mind is remembering the long arc of karma, that force which we can’t comprehend and which often falls outside of our lifetimes or limited worldly and sensorial vision. Nothing happens without the balance; we just aren’t often privileged to see it. From Seneca’s Thyestes:

The savage king who wields the scepter with cruel sway

Fears those who fear him; dread comes back to the head of the originator.

Or, if you prefer more modern-day parlance, the words of epic bard and pop-poet Taylor Swift do nicely:

Karma is a god

Karma is the breeze in my hair on the weekend

Karma's a relaxing thought

Aren't you envious that for you it's not?

Sweet like honey, karma is a cat

Purring in my lap 'cause it loves me

Flexing like a goddamn acrobat

Me and karma vibe like that

In any event, remember that it’s all a cycle. It will all come back around. And just as these writers across centuries have witnessed and captured these cycles, so too will future generations write their own verses about power, justice, and redemption. The wheel keeps turning, and the written word keeps bearing witness.

Thank you for this reminder, Sara. Much needed.